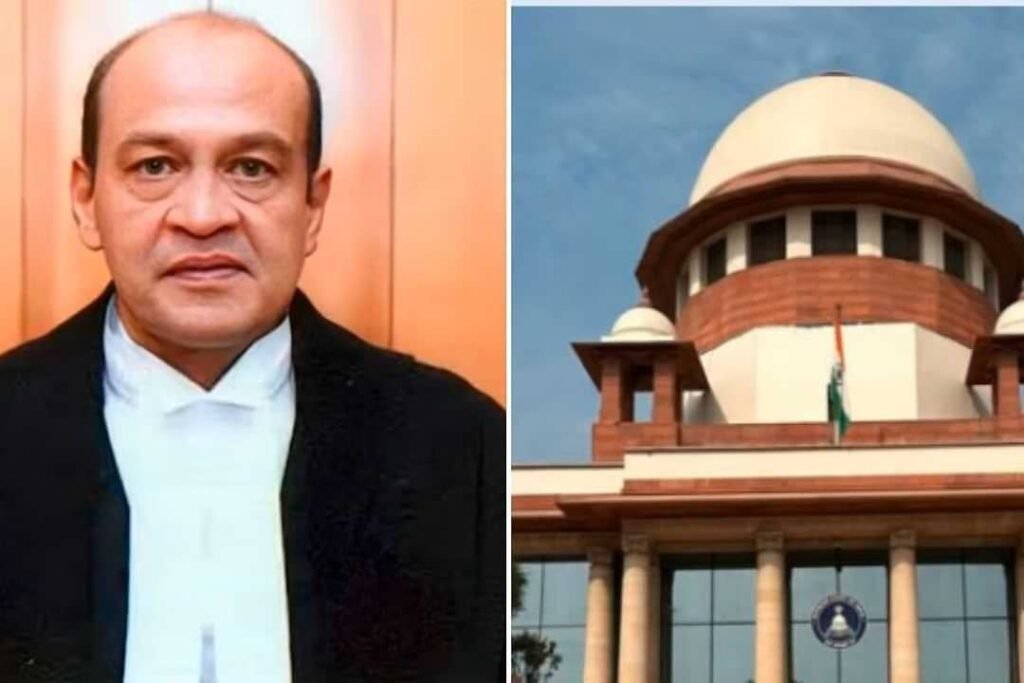

New Delhi: In a landmark ruling that reinforces the balance between judicial independence and parliamentary accountability, the Supreme Court of India on January 16, 2026, dismissed a petition filed by Allahabad High Court judge Justice Yashwant Varma. The judge had challenged the constitutionality of an inquiry committee set up by the Lok Sabha Speaker to probe allegations of misconduct linked to the discovery of burnt currency notes at his official residence in Delhi in March 2025.

A bench comprising Justices Dipankar Datta and S C Sharma held that the Lok Sabha Speaker committed “no illegality” in forming the three-member committee under the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968. The court emphatically stated that Justice Varma “is not entitled to any relief” and that “no interference” by the judiciary was warranted in the matter.

The judgment underscores a key principle: “Constitutional safeguards for judges cannot come at the cost of paralysing the removal process itself.” This observation highlights the court’s effort to prevent procedural interpretations from stalling legitimate inquiries into judicial misconduct.

Background: The Fire Incident That Sparked Nationwide Controversy

The controversy traces back to the night of March 14, 2025, when a fire broke out at the official residence of then-Delhi High Court judge Justice Yashwant Varma in New Delhi. Firefighters responding to the blaze reportedly discovered substantial amounts of burnt and half-burnt currency notes in a storeroom on the premises.

Following the incident, Justice Varma was repatriated from the Delhi High Court to the Allahabad High Court. An in-house probe by a committee constituted by the then-Chief Justice of India led to recommendations for further action, including initiation of removal proceedings.

Motions seeking the removal of Justice Varma were subsequently introduced in both Houses of Parliament on the same day. While the Lok Sabha Speaker admitted the motion and proceeded to constitute an inquiry committee in August 2025, the motion faced rejection in the Rajya Sabha under the Deputy Chairman (following the resignation of the then-Chairman Jagdeep Dhankhar).

Justice Varma’s Legal Challenge and Key Arguments

Justice Varma approached the Supreme Court, arguing that the Lok Sabha Speaker’s unilateral formation of the committee violated statutory provisions. He primarily relied on the first provision to Section 3(2) of the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968.

This proviso addresses a specific scenario: where notices of a motion for removal are given in both the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha on the same day. In such cases, no committee shall be constituted unless the motion is admitted in both Houses, and if admitted, the committee must be formed jointly by the Speaker and the Chairman.

Justice Varma contended that since notices were submitted simultaneously in both Houses, a joint committee was mandatory. He further argued that rejection of the motion in the Rajya Sabha should automatically invalidate proceedings in the Lok Sabha. Additionally, he questioned the authority of the Deputy Chairman to reject the motion in the absence of the Chairman.

Supreme Court’s Detailed Reasoning and Interpretation

The bench, in its judgment authored by Justice Dipankar Datta, rejected these contentions outright. The court clarified that the proviso to Section 3(2) applies narrowly to the situation where motions are admitted in both Houses on the same day. It does not extend to cases where a motion is admitted in one House but rejected in the other.

The judges emphasized that interpreting the proviso to impose a “disabling consequence”—where rejection in one House forces failure in the other—would amount to judicial legislation, which the court is neither empowered nor inclined to undertake.

The bench observed: “There is nothing in the Inquiry Act to suggest that rejection of a motion in one House would render the other House incompetent to proceed in accordance with law.”

On the role of the Deputy Chairman, the court referred to Article 91 of the Constitution, which empowers the Deputy Chairman to perform the duties of the Chairman when the office is vacant. The bench held that duties under the Inquiry Act are inseparable from the presiding officer’s role in the House.

The court further noted that the main provision of Section 3(2) vests independent power in the Speaker or Chairman to constitute a committee upon admission of the motion. The proviso cannot curtail this power except in the explicitly defined circumstance of simultaneous admission in both Houses.

Constitutional Framework for Removal of Judges

The ruling also delved into the broader constitutional mechanism for removing judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts.

Under Article 124 (for Supreme Court judges) and Article 218 (which applies these provisions to High Court judges), removal can only occur on grounds of proven misbehaviour or incapacity. The Constitution does not use the term “impeachment” explicitly for judges, unlike for the President.

The procedure is governed by the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968:

- Initiation: A motion must be signed by at least 100 members of the Lok Sabha or 50 members of the Rajya Sabha and submitted to the presiding officer, who decides on admission.

- Investigation: If admitted, the presiding officer refers it to a three-member inquiry committee. This comprises a sitting Supreme Court judge, a Chief Justice of a High Court, and a distinguished jurist.

- Report and Approval: The committee submits its findings to the presiding officer, who lays it before the House. If misconduct or incapacity is established, the motion proceeds to debate and requires a special majority (two-thirds of members present and voting, plus a majority of the total membership) in both Houses.

- Final Step: Removal occurs only through an order by the President.

Notably, no judge of the higher judiciary has ever been successfully removed through this process till date.

In Justice Varma’s case, the committee—comprising Supreme Court judge Justice Aravind Kumar, Madras High Court Chief Justice Manindra Mohan Shrivastava, and Senior Advocate B V Acharya—continues its work following the Supreme Court’s clearance.

Implications of the Ruling

This decision strengthens the autonomy of each House of Parliament in initiating and pursuing removal proceedings against judges. It prevents potential procedural deadlocks from derailing accountability mechanisms.

The ruling arrives amid ongoing scrutiny of judicial conduct and underscores the importance of maintaining public trust in the judiciary while respecting parliamentary privileges.

Justice Varma had earlier informed the committee that he was not present in Delhi on the day of the incident and denied responsibility for any lapses in securing the site. The Supreme Court, however, declined to intervene further.

As the inquiry proceeds, the outcome could set important precedents for future cases involving allegations against members of the higher judiciary. The balance between protecting judicial independence and ensuring accountability remains a cornerstone of India’s constitutional democracy.

FAQs

1. What was the Supreme Court’s decision regarding Justice Yashwant Varma’s plea?

On January 16, 2026, a bench comprising Justices Dipankar Datta and S C Sharma dismissed the writ petition filed by Justice Yashwant Varma. The Court ruled that the Lok Sabha Speaker committed no illegality in constituting a three-member inquiry committee under the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, to probe allegations against the judge. The bench held that Justice Varma is “not entitled to any relief” and that no judicial interference was required. The Court emphasized that constitutional safeguards for judges cannot paralyse the removal process itself.

2. What is the background of the controversy involving Justice Yashwant Varma?

The case originated from a fire incident on the night of March 14, 2025, at Justice Varma’s official residence in New Delhi (when he was a sitting judge of the Delhi High Court). Firefighters reportedly discovered substantial amounts of burnt and half-burnt currency notes in a storeroom on the premises. Following this, Justice Varma was repatriated from the Delhi High Court to the Allahabad High Court. An in-house inquiry recommended further action, leading to motions for his removal being introduced in both Houses of Parliament. The controversy raised serious questions about alleged unaccounted cash and possible misconduct.

3. Why did Justice Varma challenge the formation of the inquiry committee?

Justice Varma primarily argued that the Lok Sabha Speaker could not unilaterally constitute the committee because notices of the removal motion were submitted in both the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha on the same day. He relied on the first proviso to Section 3(2) of the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, which states that if notices are given in both Houses on the same day, no committee should be formed unless the motion is admitted in both, and if admitted, it must be constituted jointly by the Speaker and the Chairman. He further contended that rejection of the motion in the Rajya Sabha (by the Deputy Chairman after the Chairman’s resignation) should invalidate proceedings in the Lok Sabha. He also questioned the Deputy Chairman’s authority to reject the motion.

4. How did the Supreme Court respond to Justice Varma’s arguments?

The Supreme Court rejected the interpretation advanced by Justice Varma. It clarified that the proviso applies only to cases where motions are admitted in both Houses simultaneously. It does not cover situations where a motion is admitted in one House but rejected in the other. The bench stated that interpreting the proviso to create a “disabling consequence” (i.e., automatic failure in the other House) would amount to judicial legislation. The Court noted there is nothing in the Act suggesting that rejection in one House renders the other House incompetent to proceed. On the Deputy Chairman’s role, the Court referred to Article 91 of the Constitution, which allows the Deputy Chairman to perform the Chairman’s duties during a vacancy, and held that such duties under the Inquiry Act are inseparable from the presiding officer’s role.

5. What happens next in the removal process against Justice Yashwant Varma?

With the Supreme Court’s dismissal of the plea, the three-member inquiry committee—comprising Supreme Court judge Justice Aravind Kumar, Madras High Court Chief Justice Manindra Mohan Shrivastava, and Senior Advocate B V Acharya—can continue its investigation uninterrupted. The committee, formed in August 2025 by the Lok Sabha Speaker, will examine the allegations, hear witnesses, and submit a report. If the report finds proven misbehaviour or incapacity, the motion will proceed to debate in Parliament, requiring a special majority (two-thirds of members present and voting plus a majority of the total membership) in both Houses. Only then can the President issue an order for removal. This process is governed by Articles 124 and 218 of the Constitution read with the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968. No High Court or Supreme Court judge has ever been successfully removed through this mechanism to date.