New Delhi: In a landmark decision dated February 16, 2026, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) has upheld the environmental clearance for the ambitious Holistic Development of Great Nicobar Island project, dismissing multiple challenges and paving the way for one of India’s most significant strategic infrastructure initiatives in recent decades.

The six-member special bench, presided over by NGT Chairperson Justice Prakash Shrivastava and including Justices Dinesh Kumar Singh and Arun Kumar Tyagi, along with expert members A. Senthil Vel, Afroz Ahmad, and Ishwar Singh, ruled that there exists “no good ground to interfere” with the 2022 environmental clearance (EC). The tribunal emphasized the project’s undeniable strategic importance while mandating “full and strict compliance” with all EC conditions to protect the fragile island ecosystem.

Project Overview and Scale

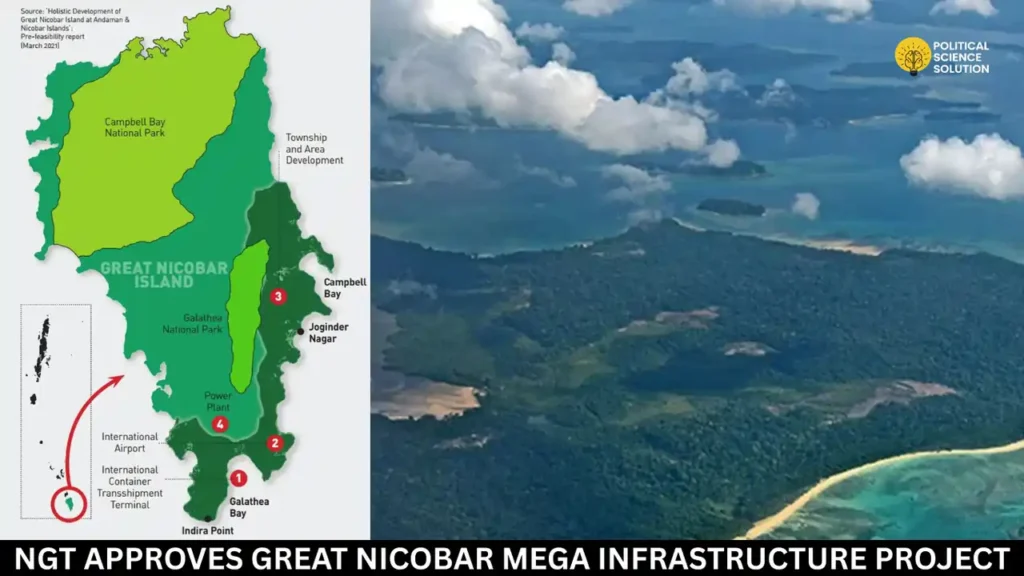

The Great Nicobar Island project, often referred to as the Holistic Development of Great Nicobar Island at Galathea Bay, spans approximately 166 square kilometers on Great Nicobar—the southernmost and largest island in the Nicobar group within the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago. Covering a total land area of about 910 square kilometers, the island remains largely uninhabited and cloaked in pristine tropical rainforest.

Key components include:

- An international container transshipment port

- A dual-use civil and military airport

- An integrated township

- A 450-MVA power plant combining gas and solar energy sources

Implementation requires diverting roughly 130 square kilometers of forest land, leading to the felling of nearly one million trees. Cost estimates vary slightly across reports, ranging from ₹81,000 crore to ₹92,000 crore, underscoring the massive scale of this endeavor.

Tribunal’s Reasoning: Balancing Strategy and Ecology

The NGT’s order addresses a batch of petitions filed primarily by environmental activist Ashish Kothari and others, including earlier challenges from Debi Goenka of the Conservation Action Trust. These pleas alleged violations of the Island Coastal Regulation Zone (ICRZ) Notification, 2019, inadequate baseline ecological data limited to a single season, threats to coral reefs and leatherback turtle nesting sites, and non-adherence to the tribunal’s 2023 directives.

Building on its previous 2023 ruling—which had flagged certain deficiencies but directed the formation of a high-powered committee (HPC) chaired by former Environment Secretary Leena Nandan—the bench relied on the HPC’s findings (presented via government affidavits, as the full report remained confidential due to strategic sensitivities). The tribunal concluded that no portion of the project falls within prohibited ICRZ-IA zones, supported by ground verification from the National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management (NCSCM).

Government commitments to revise the master plan—excluding any elements in CRZ-1A or 1B areas—further addressed coastal regulation concerns.

On biodiversity risks, the NGT accepted Zoological Survey of India (ZSI) assessments that no major coral reef systems exist in the direct project footprint, though scattered corals can be translocated and regenerated using proven methods. Directives include robust measures to protect corals along the wider coastal belt.

Specific safeguards target endangered and endemic species, including leatherback sea turtles, Nicobar megapodes, saltwater crocodiles, robber crabs, Nicobar macaques, and unique bird populations. Conditions prohibit shoreline erosion, loss of sandy beaches critical for nesting, and any adverse impacts on nesting grounds.

The tribunal stressed that foreshore developments must preserve island shorelines to avoid broader ecological ripple effects.

Regarding indigenous communities, the order notes that the project will not displace Shompen or Nicobarese tribes, whose lands suffered devastation in the 2004 tsunami. However, independent monitoring committees will oversee tribal welfare and pollution control.

To compensate for unavoidable impacts, authorities plan to establish three dedicated wildlife sanctuaries for leatherback turtles, megapodes, and corals, plus two research stations at Campbell Bay and Kamorta for ongoing biodiversity monitoring.

Strategic Imperative in a Geopolitical Hotspot

Central to the NGT’s endorsement is the project’s location—just 40 kilometers from the Malacca Strait, a vital artery carrying approximately one-third of global maritime trade. The bench referenced media analyses linking the initiative to countering China’s “string of pearls” strategy through India’s Act East policy, amid intensifying Indo-Pacific competition.

Beyond defense, the development promises to fill infrastructure gaps in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, reduce transshipment costs, enhance international trade, and create around 128,558 jobs, positioning Great Nicobar as a potential global maritime hub.

The tribunal articulated that developmental activities inevitably affect the environment, but when mitigation is robust and public benefits substantial, such projects merit approval “in larger public interest.” It cautioned against overly rigid interpretations that overlook national security and ground realities.

Reactions and Future Implications

Environmental advocates have voiced disappointment, arguing the decision risks irreversible harm to a biodiversity hotspot. Political voices, including the Congress party, described the ruling as “deeply disappointing,” citing potential ecological disasters despite ongoing concerns.

Nevertheless, the NGT made clear that clearance remains conditional. Any breach of ICRZ norms, shoreline protections, species safeguards, or other obligations during construction could trigger fresh legal action.

This ruling, marking the tribunal’s second affirmation in three years, may set a precedent for evaluating strategic ventures in ecologically sensitive zones, prioritizing balanced governance that reconciles national priorities with conservation imperatives.

As the Great Nicobar project moves forward, its success will hinge on rigorous implementation of mandated safeguards, ensuring that economic and strategic gains do not come at the expense of one of India’s most unique natural treasures.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the Great Nicobar Island project, and what does it include?

The project, officially called the Holistic Development of Great Nicobar Island at Galathea Bay, is a major infrastructure initiative on Great Nicobar—the southernmost and largest island in India’s Nicobar archipelago, spanning about 910 sq km of mostly tropical rainforest. It involves constructing an international container transshipment port, a dual-use civil and military airport, an integrated township, and a 450-MVA power plant powered by gas and solar energy. The development covers approximately 166 sq km, requiring the diversion of around 130 sq km of forest land and the felling of nearly one million trees. The estimated cost ranges from ₹81,000 crore to ₹92,000 crore.

2. What did the NGT decide on February 16, 2026, regarding the project’s environmental clearance?

A six-member special bench of the NGT, led by Chairperson Justice Prakash Shrivastava (with members Justices Dinesh Kumar Singh and Arun Kumar Tyagi, plus experts A. Senthil Vel, Afroz Ahmad, and Ishwar Singh), dismissed a batch of petitions challenging the 2022 environmental clearance (EC). The tribunal ruled there was “no good ground to interfere,” citing “adequate safeguards” built into the EC conditions and the project’s undeniable strategic importance. It disposed of the applications but directed authorities to ensure “full and strict compliance” with all EC terms, including protections for shorelines, species, and coastal zones.

3. Why did the NGT emphasize the project’s ‘strategic importance,’ and what benefits does it highlight?

The NGT stressed Great Nicobar’s location—just 40 km from the Malacca Strait, through which about one-third of global trade passes—making it geopolitically vital. It referenced India’s Act East policy to counter China’s “string of pearls” strategy in the Indian Ocean region, amid growing strategic competition. Beyond defense, the project is expected to bridge infrastructure gaps in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, reduce transshipment costs for cargo, boost international trade, create around 128,558 jobs, and position the island as a global maritime hub. The tribunal noted that while development has environmental impacts, mitigation measures justify proceeding “in larger public interest” when societal gains are substantial.

4. What were the main environmental and ecological concerns raised against the project, and how did the NGT address them?

Petitioners, including activist Ashish Kothari, alleged violations of the Island Coastal Regulation Zone (ICRZ) Notification 2019, claiming parts of the project (including up to 700 hectares) fell in prohibited ICRZ-IA zones with sensitive features like coral reefs, leatherback turtle nesting sites, and megapode bird habitats. Other issues included insufficient baseline data (limited to one season), risks to endemic species (Nicobar megapode, saltwater crocodiles, robber crabs, Nicobar macaques), and potential shoreline erosion. The NGT relied on a 2023 high-powered committee report, ground verification by the National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management (NCSCM), and Zoological Survey of India (ZSI) findings that no major coral reefs exist in the direct project area (scattered ones can be translocated). It accepted government commitments to exclude CRZ-1A/1B areas from revised plans, protect nesting beaches, prevent erosion, and regenerate corals scientifically. Specific EC conditions mandate safeguards for listed species and independent monitoring.

5. Will the project affect tribal communities, and what measures are in place for environmental offsets and oversight?

The NGT recorded that the project will not displace Shompen or Nicobarese tribal communities (whose lands were heavily impacted by the 2004 tsunami), though broader concerns about ancestral land and indirect effects persist. To offset unavoidable impacts, authorities have committed to establishing three wildlife sanctuaries (for leatherback turtles, megapodes, and corals) and two biodiversity research stations at Campbell Bay and Kamorta. Independent committees will monitor tribal welfare, pollution control, and overall compliance. The tribunal made clear that any violation of EC conditions—such as shoreline changes, species harm, or ICRZ breaches—could invite fresh legal challenges, ensuring ongoing scrutiny during implementation.