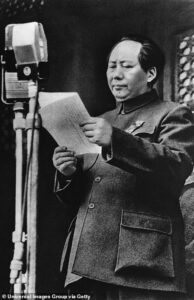

Mao Zedong, a Chinese communist revolutionary and founding father of the People’s Republic of China, was known for his radical ideology and leadership, which reshaped China through massive social and political transformations, including the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.

Introduction

Mao Zedong, often referred to as the Father of Modern Communist China, holds a unique place in the annals of history. Not only was he a revered political visionary and a transformative leader who reshaped the destiny of the Chinese people, but he also played a pivotal role in giving Marxism an Asian identity. It was under his leadership that the Communist Party of China came into existence in 1921, setting in motion a series of events that would alter the course of a nation.

The historic Long March played a very important role in establishing power of Mao. It was a strategic retreat by the Chinese Communist Party, led by Mao, from 1934 to 1935. It covered approximately 6,000 miles, through harsh terrain, to evade the Nationalist forces. The journey galvanized communist forces, solidifying Mao’s leadership, and eventually contributed to their rise to power in China.

Table of Contents

Mao Zedong’s Literary Legacy

Mao’s intellectual contributions are as significant as his political ones. Through his written works, he articulated his views on various aspects of governance and revolution. Some of his most notable works include:

On Contradiction (1937): In this piece, Mao delved into the philosophy of Dialectical Materialism, applying it to analyze different events in China through the lens of contradiction.

On Guerrilla Warfare (1937): Mao expounded on the necessity of employing guerrilla warfare tactics during the Second Sino-Japanese War, highlighting their effectiveness for the Chinese resistance.

On Practice and Contradictions (1937): Here, Mao expressed his support for Marxism and discussed the establishment of a distinct Chinese brand of communist philosophy.

On Protracted War (1938): Mao outlined his vision for a protracted people’s war as a means to challenge the authority of the state.

On New Democracy (1940): Mao introduced the concept of a dictatorship involving four social classes: the peasantry, proletariat, petite bourgeoisie, and national bourgeoisie.

On Coalition Government (1945): This was a crucial political report by Mao Zedong to the Seventh National Congress of the Communist Party of China.

On People’s Democratic Rule (1949): Written to commemorate the 28th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, this work highlighted Mao’s evolving political philosophy.

Political Ideology of Mao

Mao’s political ideology was characterized by several distinctive features, each tailored to the unique circumstances of China.

Modification of Marxism for Chinese Context

One of Mao’s most significant contributions was his attempt to adapt Marxist-Leninist ideology to align with the nuances of Asian culture. During his era, China’s economy primarily relied on agriculture and lacked the industrial foundation that Russia possessed during its revolution. Mao firmly believed that for the revolution to succeed in China, it was essential to reinterpret Marxism to better fit Chinese cultural contexts. To achieve this goal, he devised a strategy tailored to the specific conditions of his time.

In contrast to Marx and Lenin, who advocated for workers leading the revolution, Mao asserted that the leadership should come from the peasants, who comprised seventy percent of China’s rural population.

Read More about Marx – Karl Marx: Class Struggle, Historical Materialism and Communism

Belief in Permanent Revolution

In contrast to Marx’s viewpoint, which posited that the dictatorship of the proletariat was a temporary phase destined to lead to the eventual withering away of the state, Mao stated that the phase of dictatorship of the proletariat would last for a long time.

He asserted that the Revolution on the economic front must be accompanied by the political and ideological revolution as well. Mao thus believed in the perpetual character of the revolution. According to him the road to socialism must be constantly punctuated with violence.

People’s War

Central to Mao’s political thought was the concept of People’s War. He argued that revolution was required on two fronts: the overthrow of imperial powers and the end of feudal landlord rule. Mao stressed that people, not weaponry, were the decisive factor in warfare. Mao thus stressed on the theory of a total revolution by the totality of the masses – Mass line Populism.

Mao assigned a prominent role to peasants in the revolution against both imperial powers and feudal lords. He believed that even peasants could independently lead revolutionary actions, replacing the Marxist concept of the “Dictatorship of the Proletariat” with the principle of “People’s Democratic Dictatorship.”

On Contradiction

Mao Zedong’s essay “On Contradiction,” written in 1937, elaborates on his dialectical materialist philosophy. Mao argued that contradictions are inherent in all aspects of reality, and understanding and harnessing these contradictions are essential for revolutionary change. He identified two types of contradictions: antagonistic and non-antagonistic.

Antagonistic contradictions involve opposing forces in direct conflict, such as the class struggle between the peasants and aristocrat class. These contradictions can only be resolved through revolutionary means.

Non-antagonistic contradictions are less intense and can be resolved through non-violent methods, such as negotiation or persuasion. Mao believed that recognizing the distinction between these two types of contradictions was crucial for effective leadership and strategy.

Mao’s “On Contradiction” emphasized the dynamic and evolving nature of contradictions, arguing that they were not static but evolved over time. It became a foundational text for Chinese Communist ideology and had a significant influence on Mao’s leadership during the Chinese Revolution and subsequent policies. Mao in this regard also gave a speech in 1957 – “On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People’.

Guerilla Warfare: A Prolonged Revolution

While Marx and Lenin advocated for short-lived violent revolutions, Mao had a different vision for the less developed world. He believed that revolution in such regions required a prolonged struggle. To achieve this, he championed the technique of Guerrilla warfare. The primary goal of Guerrilla warfare, according to Mao, was not just to defeat the enemy but also to win the support of the people.

He understood that political victory was just as crucial, if not more so, than military success. In his words, “the most important victory is to win over the people.”

Power and War: A Barrel of Gun

Mao was a staunch advocate of the concept of Power and War. He stated that ‘political power grows out of the barrel of the gun.’ Mao attached a great importance to the power of the army. According to him, the armed bourgeoisie and the feudal lords cannot be defeated except by the power of the gun. Mao asserted that War alone could bring an end to capitalism and install communism.

New Democracy: A Different Democratic Vision

Mao’s concept of New Democracy was a departure from the Western model of “Representative Democracy,” which he referred to as “Old Democracy.” He believed that in colonial and semi-colonial countries, the democratic system should adapt to the unique social and economic conditions of the region.

His New Democracy involved the participation of four social blocs: the peasantry, proletariat (working class), petite bourgeoisie (middle class), and national bourgeoisie (national capitalists). This model, often called the “Dictatorship of Four Classes,” aimed to create a new form of democracy tailored to the needs of these countries. He believed that the function of the state is to remove obstacles to freedom.

Cultural Revolution: Empowering the Masses

In a bid to diminish the role of the party and elevate the influence of the masses, Mao initiated the Grand Proletarian Cultural Revolution in 1965-66. This revolutionary movement sought to protect Chinese Marxist society from the industrialization and bureaucratization trends prevalent in Western societies.

Mao’s supporters, known as the Red Guards, primarily composed of students, traversed the country, spreading Mao’s ideology and carrying the Little Red Book, which contained his thoughts.

Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward was a socio-economic campaign initiated by Mao Zedong, the leader of the People’s Republic of China, in the late 1950s. It aimed to rapidly transform China from an agrarian society into an industrial and collective farming powerhouse. However, in reality, it resulted in a humanitarian disaster.

The campaign emphasized mass mobilization and the establishment of communes, where agricultural and industrial activities were collectivized. This led to the loss of individual land ownership and property, causing widespread famine and suffering. The government’s unrealistic production targets and policies such as backyard steel production also led to inefficiencies and economic collapse.

Between 1958 and 1962, tens of millions of people died due to starvation and the harsh living conditions imposed by the Great Leap Forward. It also had long-lasting economic repercussions, setting China back several years.

Let Hundred Flowers Bloom: A Cultural Revolution Endeavor

During the Cultural Revolution, in May 1956 Mao Zedong introduced a noteworthy policy known as the “Hundred Flowers Bloom”. This policy challenged the notion that a society should adhere to a single ideology or state. Mao’s perspective was refreshing: he likened different ideologies and thoughts to individual flowers in a vast garden, encouraging the proliferation of diverse viewpoints.

In essence, he championed the idea that society should embrace a multitude of ideas, even if they contrasted with the prevailing ones. Through this theory, Mao aimed to cleanse society of antiquated and decaying notions, emphasizing the importance of freedom of expression for a flourishing intellectual landscape.

Quotes by Mao Zedong

- “Politics is war without blood, while war is politics without blood.”

- “Political power grows out of the barrel of the gun.”

- “History is the symptom of our disease.”

- “You can’t be a revolutionary if you don’t eat chilies.”

- “Historical experience is written in iron and blood.”

- “War can only be abolished through war, and in order to get rid of the gun, it is necessary to take up the gun.”

- “An army of the people is invincible.”

Conclusion

Mao’s unwavering belief in the collective wisdom of the masses led him to emphasize the importance of the Communist Party’s receptiveness to learning from the lower echelons of society. He undertook the task of adapting Marxism to align with China’s predominantly rural and oriental character. As a result, he is widely celebrated for his role in transforming Marxism from its European origins into a distinctly Asian manifestation. Mao’s legacy stands as a testament to the power of his vision and his ability to bridge the gap between ideology and the realities of a diverse and complex society.

Read More: