New Delhi: In a groundbreaking moment for marine conservation, Morocco’s ratification on September 19, 2025, marked the 60th nation to endorse the High Seas Treaty, officially triggering its enforcement. This pivotal agreement, formally known as the Agreement on Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement), will come into effect in January 2026, exactly 120 days after Morocco’s decisive action. The treaty, adopted in 2023 by the Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, represents a monumental step toward safeguarding the vast international waters that span nearly two-thirds of the world’s oceans.

A Global Commitment to Ocean Protection

The High Seas Treaty operates under the framework of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), joining two other implementing agreements: the 1994 Agreement on UNCLOS implementation and the 1995 United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement. The treaty’s activation required ratification by 60 nations, a milestone achieved in what experts call “record time” for such a complex international accord. Elizabeth Wilson, senior director for environmental policy at The Pew Charitable Trusts, noted at a recent UN Oceans Conference that parliamentary approvals for such treaties often take over five years, making this rapid progress remarkable.

The high seas, defined as areas beyond any nation’s jurisdiction, are global commons open to all for activities like navigation, overflight, and laying submarine cables. However, these waters, covering nearly half of Earth’s surface, have been largely unregulated, leaving them vulnerable to overfishing, pollution from shipping, and climate-driven ocean warming. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) reports that nearly 10% of assessed marine species face extinction risks, with only 1% of the high seas currently under protection.

India’s Role and Global Support

India has demonstrated its commitment to ocean stewardship by approving the signing of the High Seas Treaty in 2024, with the Ministry of Earth Sciences tasked with its implementation. This move aligns with global efforts to protect marine ecosystems, as emphasized by United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres: “Covering more than two-thirds of the ocean, the agreement sets binding rules to conserve and sustainably use marine biodiversity.”

The treaty’s activation aligns with the global “30×30” pledge, established three years ago, to protect 30% of the world’s land and sea by 2030. This target aims to restore depleted marine populations, and the High Seas Treaty provides a legal framework to designate marine protected areas (MPAs) in international waters. Countries can now propose specific zones for protection, which will be voted on by treaty signatories during conferences of the parties (COPs).

Challenges in Protecting the High Seas

Protecting the high seas is inherently complex due to their status as shared global resources. No single nation governs these waters, where all countries have rights to fish and navigate. Johan Bergenas, senior vice president of oceans at the World Wildlife Fund, described the high seas as “the world’s largest crime scene—unmanaged, unenforced, and a regulatory legal structure is absolutely necessary.” He highlighted the logistical challenges ahead: “You need bigger boats, more fuel, more training, and a different regulatory system. The treaty is foundational—now begins the hard work.”

The treaty’s enforcement relies on individual nations regulating their own vessels and companies. For example, if a German-flagged ship violates regulations, Germany is responsible for enforcement. Torsten Thiele, founder of the Global Ocean Trust, emphasized the importance of universal ratification: “If somebody hasn’t signed up, they’ll argue they’re not bound.” This raises concerns, as major maritime powers like the United States, China, Russia, and Japan have yet to ratify. While the U.S. and China have signed the treaty—indicating alignment with its goals without legal obligations—Russia and Japan have only engaged in preparatory talks.

Guillermo Crespo, a high seas expert with the IUCN commission, warned, “If major fishing nations like China, Russia, and Japan don’t join, they could undermine the protected areas.” The treaty’s lack of a dedicated enforcement body further complicates compliance, as nations conduct their own environmental impact assessments and make final decisions, though others can raise concerns through monitoring mechanisms.

A Catalyst for Collaboration

Environmental leaders have hailed the treaty’s activation as a historic achievement. Kirsten Schuijt, director-general of the World Wide Fund for Nature, called it “a monumental achievement for ocean conservation” and a “turning point for two-thirds of the world’s ocean that lie beyond national jurisdiction.” Mads Christensen, executive director of Greenpeace International, described it as “proof that countries can come together to protect our blue planet,” urging swift action: “The era of exploitation and destruction must end. Our oceans can’t wait, and neither can we.”

The treaty establishes frameworks for technology-sharing, funding, and scientific collaboration, ensuring equitable access to ocean resources. It also regulates high-impact activities like deep-sea mining and geoengineering, which pose significant risks to marine ecosystems. Within a year of the treaty’s entry into force, ratifying nations will convene to finalize implementation, financing, and oversight details, with only those who ratify beforehand holding voting rights.

The Ocean’s Critical Role

The ocean is Earth’s largest ecosystem, contributing an estimated $2.5 trillion (£1.9 trillion) annually to global economies and producing up to 80% of the oxygen we breathe. It plays a vital role in climate regulation by absorbing heat and carbon dioxide. Lisa Speer, director of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s international oceans program, underscored the interconnectedness of marine ecosystems: “Marine life doesn’t respect political boundaries. Fish, turtles, seabirds, and other species migrate across the ocean, so what happens in the high seas affects coastal waters.”

For small island nations like Vanuatu, the treaty offers unprecedented influence in global ocean governance. Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu’s Minister for Climate Change, stated, “Everything that affects the ocean affects us.” These nations, often the most vulnerable to ocean changes, now have a voice in decisions previously beyond their reach.

Concerns and Future Outlook

Despite the optimism, some experts caution that the treaty’s impact may be limited without universal participation. Enric Sala, founder of National Geographic’s Pristine Seas project, warned that some nations might use the treaty to justify inaction in their own waters: “There are countries that are using the process to justify inaction at home.” Sylvia Earle, a renowned ocean explorer, framed the ratification as a “way station—not the end point,” urging leaders to address ongoing overexploitation: “If we continue to take from the ocean and use it as a dump site, we’re putting fish, whales, krill, and ultimately ourselves at risk.”

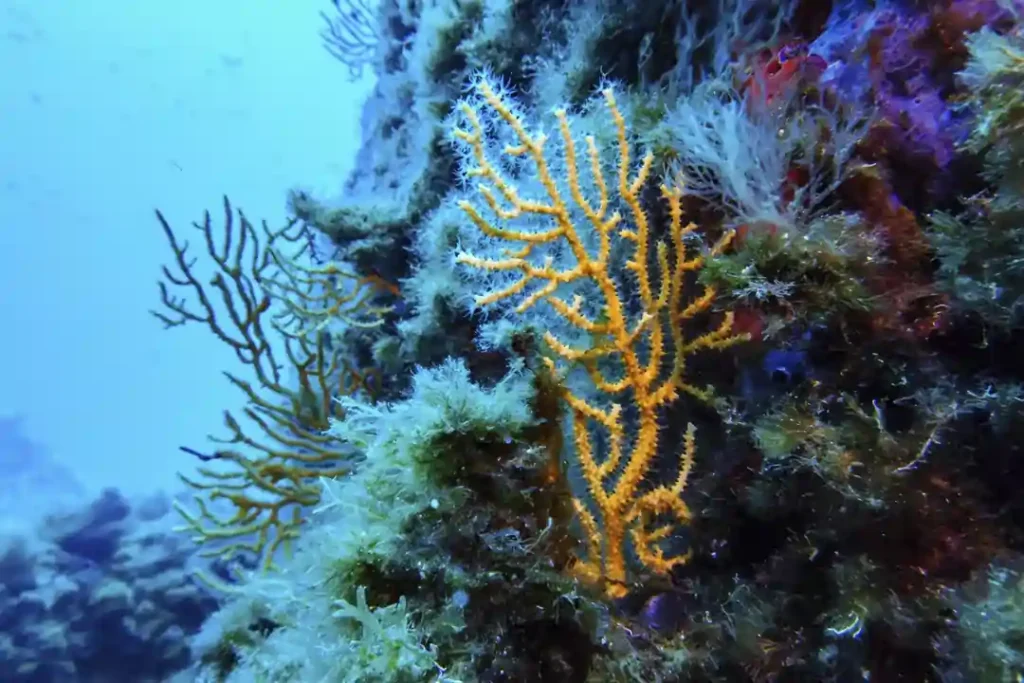

Visual reminders of what’s at stake, such as vibrant coral reefs in France’s Porquerolles National Park photographed by Annika Hammerschlag ahead of the UN Ocean Conference on June 6, 2025, highlight the urgency of protection efforts. As the treaty prepares to take effect, the focus shifts to building robust monitoring and compliance systems. The High Seas Treaty stands as a beacon of hope, but its success depends on global cooperation and diligent execution to reverse decades of ocean decline and secure a sustainable future.

FAQs

1. What is the High Seas Treaty, and why is its activation significant?

The High Seas Treaty, formally known as the Agreement on Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement), is a legally binding treaty under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Adopted in 2023, it aims to protect marine biodiversity in international waters, which cover nearly two-thirds of the world’s oceans. Morocco’s ratification on September 19, 2025, marked the 60th nation to endorse it, triggering its enforcement in January 2026 after a 120-day countdown. This milestone is significant because it establishes a legal framework to create marine protected areas (MPAs), regulate activities like deep-sea mining, and promote global cooperation to combat overfishing, pollution, and climate-driven ocean damage.

2. What are the high seas, and why do they need protection?

The high seas are areas of the ocean beyond any country’s national jurisdiction, constituting nearly half of Earth’s surface. These global commons are open to all nations for activities like navigation, fishing, and laying submarine cables. However, they face severe threats from overfishing, shipping pollution, and climate change, with only 1% currently protected. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) reports that nearly 10% of marine species are at risk of extinction. Protecting the high seas is critical as they regulate Earth’s climate, absorb carbon dioxide, produce up to 80% of the oxygen we breathe, and contribute $2.5 trillion annually to global economies.

3. How does the High Seas Treaty work, and what are its key features?

The treaty provides a framework for conserving and sustainably using marine biodiversity in international waters. Key features include establishing marine protected areas (MPAs) through proposals and votes by signatory nations at conferences of the parties (COPs), regulating high-impact activities like deep-sea mining and geoengineering, and fostering technology-sharing, funding, and scientific collaboration. Enforcement relies on countries regulating their own vessels and companies, with no dedicated punitive body. The treaty supports the global “30×30” goal to protect 30% of land and sea by 2030, ensuring marine ecosystems can recover.

4. What challenges does the High Seas Treaty face in implementation?

Implementation faces several hurdles. The treaty depends on individual nations to enforce regulations on their ships and companies, which may lead to inconsistencies. Major maritime powers like the United States, China, Russia, and Japan have not yet ratified, raising concerns about compliance, as non-ratifying nations may claim they are not bound. Critics also note that countries conduct their own environmental impact assessments, potentially weakening oversight. Additionally, some nations might use the treaty to delay conservation efforts in their own waters, as warned by Enric Sala of National Geographic’s Pristine Seas project.

5. How does the High Seas Treaty impact small island nations and global cooperation?

For small island nations like Vanuatu, the treaty offers a voice in global ocean governance, which has historically been out of their reach. Vanuatu’s Minister for Climate Change, Ralph Regenvanu, emphasized, “Everything that affects the ocean affects us.” The treaty fosters multilateral decision-making through COPs, ensuring equitable participation. It also promotes scientific and financial collaboration, helping less-resourced nations benefit from ocean conservation. Environmental leaders, including Greenpeace’s Mads Christensen, view the treaty as proof that countries can unite for planetary protection, though universal ratification remains crucial for its success.