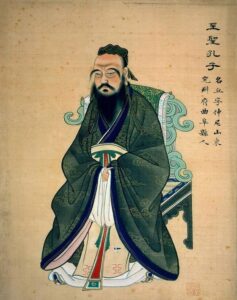

Confucius, an ancient Chinese philosopher, emphasized moral values and harmonious social relationships as the foundation for a just and orderly society.

Introduction

Confucius, also known as Kung Fu-Tzu or Kong Fu-zi, which translates to “Master Kung,” was born in the cradle of ancient China in 551 BC. Beyond being a thinker and political figure, he held the esteemed title of China’s first teacher and was the founding luminary of the Ru School of Chinese Thought. Confucius’ ideas, centered on the pursuit of social and political harmony through principled governance, fostering proper human relations, and nurturing individual moral development, have left an indelible mark on Chinese society, enduring for centuries.

Table of Contents

Historical Background

Confucius’ life unfolded during a tumultuous era in China’s history, marked by a pervasive sense of moral and social disarray. It was this pervasive disorder that ignited the flame of reform in Confucius’ heart. Driven by a fervent desire to restore cultural and political order, he embarked on a mission to enlighten society through education and the dissemination of his profound philosophy.

Primary Sources of Confucian Thought

At the core of Confucian thought lay a deep reverence for the wisdom of the past, which he believed could guide the present and shape the future. He attributed his teachings to the wisdom of the “Ancients,” encapsulated in “The Five Classics” (Wu Jing):

- The I Jing (Book of Changes): Exploring the dynamics of change and the interconnectedness of all things.

- The Shu Jing (Book of History): Unraveling the tapestry of China’s historical narratives.

- The Shih Jing (Book of Odes [poetry]): Elevating the power of poetic expression to convey moral truths.

- The Li Ji (Book of Rites): Prescribing the rites and rituals that underpin a harmonious society.

- The Ch’un-ch’iu (Spring and Autumn Annals): Chronicling the historical events of the state of Lu, Confucius’ homeland.

Further enriching the treasury of Confucian wisdom are “The Four Books” (Ssu-chu), a compendium of Confucius’ teachings and those of his devoted disciples:

- Analects: A collection of Confucius’ sayings and ideas, offering profound insights into ethics and governance.

- The Doctrine of the Mean: Expounding the concept of moderation as a path to virtue.

- The Great Learning: Providing guidance on the pursuit of wisdom and self-improvement.

- The Book of Meng-Tzu: Elaborating on the teachings of Confucius and their practical applications.

Views on Education

In the eyes of Confucius, the light of education should shine upon all, irrespective of their social status. He championed the cause of universal education, believing that it should encompass not only the acquisition of knowledge but also the cultivation of love and appreciation for one another—what we now recognize as “moral education.”

The Five Constant Virtues

Central to Confucian philosophy are the Five Constant Virtues, the very bedrock upon which a harmonious society is built. These virtues are:

- Benevolence/Humanity (Ren): The essence of compassion that binds us all.

- Propriety (Li): Guiding our social and moral behavior.

- Righteousness/Justice (Yi): The moral compass that leads us towards what is right and just.

- Wisdom/Knowledge (Zhi): The pursuit of truth and understanding.

- Trustworthiness/Integrity (Xin): Upholding a steadfast commitment to moral character.

Universal Golden Rule

In Confucius’ ethical framework, the virtue of Ren, or humanity, takes center stage, harmonizing with two essential principles:

- Zhong: The embodiment of the positive practice or the “Golden Rule” of Ren, advocating treating others as we wish to be treated.

- Shu: The embodiment of the negative practice or the “Silver Rule” of Ren, cautioning against treating others in ways we would not desire for ourselves.

The Five Relationships

In the tapestry of Confucian philosophy, threads of wisdom weave together to form a rich fabric of societal harmony and order. At the heart of Confucius’ teachings lies a profound emphasis on relationships and their pivotal role in maintaining social equilibrium.

Confucius believed that a well-ordered society rested upon the foundation of five fundamental relationships, each governed by its unique set of virtues:

Father – Son: The bond of filial piety, emphasizing respect and obedience from the child to the parent.

Ruler – Subject: Rooted in loyalty, this relationship calls for unwavering allegiance from the subject to the ruler.

Elder Brother – Younger Brother: Characterized by brotherliness, this bond fosters a sense of camaraderie and mutual support among siblings.

Husband – Wife: Love and obedience are the cornerstones of this relationship, promoting harmony within the family unit.

Friend – Friend: Friendship is grounded in faithfulness and equality, nurturing bonds of trust and solidarity among peers.

These relationships are underpinned by a fundamental concept: the existence of inferior and superior roles. According to Confucius, the key to societal order is the unwavering fulfillment of one’s role within these relationships. This commitment to role fulfillment serves as a guiding principle, steering society away from chaos and towards harmony. As Confucius succinctly puts it, “A country would be well-governed when all the parties performed their parts alright in these relationships.”

The Gentleman (Junzi): An Exemplary Figure

In Confucius’ political thought, the Gentleman, known as Junzi, emerges as the embodiment of the ideal individual. The Junzi possess a deep understanding of the intricacies of these relationships and uphold the proper rituals associated with them. He is not a commander or ruler, but rather a moral paragon who leads by virtue of his character and conduct.

The Junzi is a cultured individual who navigates social situations with grace and wisdom. Through personal example and service in government, he promotes a way of living that is in perfect alignment with a well-ordered society.

Good Government: The Rule of Virtue

Confucius envisioned a government that transcended mere politics—a government characterized by moral excellence. According to his teachings, a good government embodies the following principles:

- Humane Government: Governed by compassion and empathy, a humane government prioritizes the well-being of its people.

- Guided by Virtue: Virtue serves as the compass guiding the actions and decisions of a just ruler.

- Government by Moral Example: The government sets the standard for ethical behavior, inspiring its citizens to follow suit.

Key factors essential to good governance, as outlined by Confucius, include ensuring an ample food supply for the people, maintaining a strong and capable army, and fostering the confidence of the populace in the ruler.

Quotes by Confucius

- “By three methods we may learn wisdom: First, by reflection, which is noblest; Second, by imitation, which is easiest; and third by experience, which is the bitterest.”

- “The man who asks a question is a fool for a minute, the man who does not ask is a fool for life.”

- “Give a bowl of rice to a man and you will feed him for a day. Teach him how to grow his own rice and you will save his life.”

- “The man of wisdom is never of two minds; the man of benevolence never worries; the man of courage is never afraid.”

- “Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself.”

- “Education breeds confidence. Confidence breeds hope. Hope breeds peace.”

Conclusion

Confucianism has been the chief cultural influence of China for centuries. Confucius has deeply influenced the spiritual and political life of China. His ethics and philosophy has deep universal applicability to modern relationships and societies throughout the world.

Read More:

- Public Policy Part 2 | UGC NET & CUET PG Political Science Video Lecture

- Public Policy Part 1 | UGC NET Political Science & CUET PG Video Lecture

- Preamble of Indian Constitution | UGC NET & CUET PG Political Science Video Lesson

- India’s Leading States Push for Social Media Bans on Children: Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh Lead the Charge Amid Global Concerns

- Parliament of India – 45 MCQs for UGC NET | CUET PG

I have been examinating out a few of your articles and i can state clever stuff. I will definitely bookmark your blog.