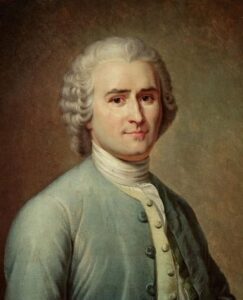

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was an 18th-century French philosopher known for his ideas on social contract theory and the belief in the innate goodness of humans, while also advocating for a more egalitarian society.

Introduction

Born on June 28, 1712, in the picturesque city of Geneva, Jean-Jacques Rousseau emerged as a pivotal figure during the Enlightenment era, leaving an indelible mark on the intellectual landscape of his time. Often referred to as the intellectual Father of the French Revolution, Rousseau was a trailblazer who challenged established norms and institutions in the pursuit of modern values such as equality, liberty, and democracy.

Rousseau’s philosophy underscores the profound distinction between society and human nature. He posited that in the state of nature, humans were inherently good but became corrupted by the artificial constructs of society, particularly critiquing the concept of private property. Additionally, he championed the idea of human equality within society and aimed to harmonize liberty and equality. Rousseau also advocated the concept of the General Will as the true foundation of legitimate power and authority, all while advocating simplicity, innocence, and virtue as the means to unlock the full potential of human nature. His philosophy resonated deeply with those who yearned for a return to a more natural and unspoiled existence, free from the trappings of modern society.

Table of Contents

Early Life of Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born into a poor family in Geneva, with his mother dying shortly after his birth. His father struggled to provide a coherent upbringing, and at the age of twelve, Rousseau was apprenticed to various masters but failed to establish himself in any trade. Throughout his life, he lived in poverty, relying on his ingenuity and the generosity of women. For material advantages, he even changed his religion and accepted charity from people he disliked.

In 1744, Rousseau moved to Paris, where he explored various fields, including theatre, opera, music, and poetry, but achieved little success. Despite this, his charismatic personality allowed him to gain access to the prestigious salons of Paris, where he mingled with leading encyclopedists and influential women, some of whom he had close relationships with. However, he distanced himself from the upper class, maintaining the values of his low-middle-class, puritanical upbringing.

During Rousseau’s lifetime, France was ruled by the absolutist regime of Louis XV, where political power and social prestige were monopolized by the king, clergy, and nobility, who lived extravagantly at the expense of the struggling masses. The corrupt bureaucracy denied even basic needs, fostering widespread discontent and a desire for change. The emerging bourgeoisie, feeling restricted by the current order, allied with the peasantry to seek reform.

The French Enlightenment significantly influenced the climate of dissent against the ancien régime, emphasizing reason and experience. While Rousseau aligned with some Enlightenment ideas, he diverged in his emphasis on feelings over rationality. He believed modern man had lost touch with his emotions, leading him to reject the Enlightenment’s prioritization of reason and advocating for a more emotional connection to humanity.

His Major Works

Rousseau’s intellectual contributions manifested through a series of influential writings that challenged conventional wisdom and ignited fervent debates:

Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (1750): In this work, Rousseau provocatively asserted that ‘Our souls have been corrupted in proportion to the advancement of our sciences and our arts towards perfection’.

Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality (1755): Rousseau’s second discourse delved into the origins of inequality, tracing it back to the establishment of civil society and the emergence of private property.

Discourse on Political Economy (1755): This discourse explored the concept of democratic ideals, further solidifying Rousseau’s commitment to the principles of equality and liberty.

Emile (1762): Rousseau’s treatise on education, Emile, had a profound impact on the development of the French education system during the tumultuous period of the French Revolution.

The Social Contract (1762): In this magnum opus, Rousseau expounded on the concept of the General Will as the cornerstone of legitimate authority, presenting a vision of a just social contract that resonated with revolutionary thinkers of his time.

Essay – “Has the progress of sciences and arts contributed to corrupt or purify morals” – For this particular essay Rousseau also won a prize in 1749 sponsored by the Academy of Dijon.

The Confession – Autobiography of Rousseau

Revolt Against Reason

During the Enlightenment, a time of great scientific advancement and the belief in reason as the guiding principle of life, Jean-Jacques Rousseau emerged as a critical voice. He challenged the Enlightenment’s focus on intelligence, science, and reason, claiming that these elements were harming the faith and moral values of society. Rousseau believed that the “thinking animal is a depraved animal,” arguing that reason suppressed natural feelings like sympathy and compassion. He contended that reason led to pride, which conflicted with sympathy, and he viewed pride as inherently evil. In his book Political Thought, Wayper stated, “Rousseau, ardent apostle of reason, has done more than most to prepare the way for the age of unreason in which he lived.”

Rousseau’s criticism of the Enlightenment was articulated in a prize-winning essay written in 1749, where he addressed the question, “Has the progress of science and arts contributed to corrupt or purify morality?” He argued that science did not enhance morality but rather caused moral decline. Rousseau believed that what was perceived as progress was, in fact, a regression. He asserted that the arts of civilized society merely adorned the chains that bound people. In his view, modern civilization did not make people happier or more virtuous; instead, it corrupted them, with greater sophistication leading to greater corruption.

He was skeptical of the Baconian dream of creating abundance on Earth, believing that abundance led to luxury, which was a known source of corruption. Rousseau pointed to historical examples, stating that Athens fell because of its luxury and excess, and that Rome lost its strength after becoming wealthy and indulgent. He argued, “Our minds have been corrupted in proportion as the arts and sciences have improved.” For Rousseau, the praised civility and refinement of society concealed negative traits such as jealousy, suspicion, and deceit.

Against the Enlightenment’s faith in intelligence and progress, Rousseau promoted kindness, goodwill, and moral feelings. He argued that sentiments and conscience should guide moral values. He believed that without reverence, faith, and moral intuition, there could be no character or society. Rousseau saw modern society as false and artificial, having strayed from a true culture that reflects genuine human nature and the collective will of the people.

Rousseau’s Political Philosophy

State of Nature

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s political philosophy takes us on a journey back to the origins of human existence, challenging the conventional wisdom of his time. According to Rousseau, in the state of nature, individuals were guided by instinct rather than reason. He painted a vivid picture of noble savage i.e. living in idyllic bliss, leading lives characterized by independence, self-sufficiency, and a profound connection with nature. In this pristine state, happiness was not contingent on reason but thrived in simplicity, free from the artificial desires that reason often gave birth to. He further quoted – ‘A happy individual was not much a thinking being’.

Rousseau’s critique of reason was rooted in the belief that it led to the unquenchable desires of individuals, making them perpetually unhappy. The more one embraced reason, the more their desires multiplied, creating a cycle of discontentment.

“Rousseau observed that although life was peaceful in the state of nature, People were unfulfilled” – Edward W. Younkins

The Emergence of Private Property

The advent of civilization, marked by the discovery of metals and agriculture, brought about the division of labor and the rise of private property. He asserts that the cultivation of land resulted in property claims, famously remarking, “The first man who after felling off a piece of land, took it upon himself to say ‘This belongs to me,’ and found people simple-minded enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society.” With the concept of property came inequality, as differences in talents and skills led to varied fortunes. Wealth enabled some individuals to enslave others, provoking competition and conflict. This conflict created a demand for a legal system to maintain order, particularly from the wealthy, who feared losing their possessions in a state of violence.

According to Rousseau, this demand resulted in the formation of civil society and laws that imposed new constraints on the poor while empowering the rich. He claimed that these developments destroyed natural liberty, established laws of property and inequality, and transformed wrongful usurpation into accepted rights, subjecting humanity to labor, servitude, and misery for the benefit of a few ambitious individuals.

Rousseau argued, however, that things need not have turned out so poorly. He suggested that when men willingly entered chains with the establishment of government, it was because they recognized the advantages of political institutions without the experience to foresee their potential dangers. This idea would be revisited in his later work, Social Contract. It is crucial to note that Rousseau did not depict the transition from the state of nature to civil society as a historical fact; rather, he employed hypothetical reasoning to explore the nature of humanity and society, rather than ascertain their actual origins.

Analyzing Inequality

Rousseau’s analysis of inequality was rooted in the stark contrast between the natural state of individuals—pure, good, and roughly equal to one another—and their corrupted, unequal, and degraded state within society. He classified inequality into two types – Natural inequality (Based on birth, skills, talent, age, sex etc) and Conventional equality (Constructed by society primarily with the advent of private property).

He further advocated for social equality, although not absolute equality, permitting distinctions based on contributions to society and natural factors like age and wealth.

Concept of “General Will”

Rousseau posited that the General Will should serve as the foundation for all laws, with its embodiment realized through direct democracy. He distinguished between the actual will, driven by immediate self-interest, and the real will, which is motivated by the collective good. The General Will functions as a unifying force, aligning individual interests with those of the community, thereby crucial for achieving social and political equality.

He emphasized that the General Will must genuinely originate from and focus on the common good, ensuring that decisions involve every member of society. Rousseau viewed economic equality as essential for preserving individual liberty and attaining true social and political equality.

However, critics have described Rousseau’s concept of the General Will as “forced to be free.” Scholar Jacob Talmon labeled Rousseau a “totalitarian democrat,” while Bosanke argued that Rousseau’s theory misleads readers by establishing sovereignty on an uncertain foundation. By making the General Will sovereign and viewing individuals as participants in it, Rousseau reconciled authority with freedom more effectively than his predecessors.

In his Discourse on Political Economy, Rousseau stated that the General Will aims for the preservation and welfare of both the whole and each part, serving as the source of laws. He differentiated it from the “will of all,” which merely aggregates private interests. The General Will is not merely a numerical majority but reflects moral quality and goodness, emerging when individuals sacrifice personal interests for the collective good.

Rousseau recognized that unanimity on the General Will may not always be possible, as individuals might not fully understand the common good. He suggested that if one removes conflicting particular interests from individual wills, what remains is the General Will.

Moreover, he asserted that those who refuse to obey the General Will would be “forced to be free.” This compulsion is justified, he argued, because individuals have already consented to be governed by the social contract, which promotes their long-term interests. In essence, obeying the General Will reflects an individual’s moral freedom, representing rational self-governance that aligns with the common good. Thus, when the General Will prevails, individuals should not perceive it as a loss of liberty but as adherence to their rational self.

The Social Contract Theory

In his influential work, The Social Contract, Rousseau proposed that a political community should protect the general interests of its members while transforming the noble savage into a cooperative and humane member of society. He asserted that liberty is the most cherished possession of individuals, and the right kind of society could enhance this freedom by governing through what he called the “General Will.”

For Rousseau, the social contract was a method to reconcile liberty with authority, where consent served as the foundational principle. He emphasized that a community exists to serve the individual by safeguarding their freedom. This community reflects the collective best interests of all its members, operating in harmony with the General Will, which represents the shared will of individuals thinking beyond their self-interests.

While Rousseau criticized ‘civil society’, he did not advocate for a return to a savage existence, as some of his contemporaries misinterpreted him. For instance, Voltaire mocked Rousseau’s ideas, suggesting he wanted people to revert to walking on all fours. In the Discourse, Rousseau exclaimed, “What then is to be done? Must societies be totally abolished? Must meum and tuum be annihilated, and must we return again to the forests to live among bears? This is a deduction in the manner of my adversaries, which I would as soon anticipate and let them have the shame of drawing.”

Rousseau believed there was no going back to the state of nature. He argued that society is inevitable; without it, humanity could not fulfill its potential. His critique of civil society was rooted in its unjust foundations and corrupting influences. Therefore, he aimed to create a new social order that would enable individuals to realize their true nature.

To this end, Rousseau dedicated himself in The Social Contract. He sought to address the issue of political obligation, asking why individuals should obey the state through a proper reconciliation of authority and freedom. He felt that previous philosophers had inadequately tackled this critical task. The Social Contract opens with the powerful declaration, “Man is born free, and he is everywhere in chains.” Rousseau’s goal was to legitimize the chains of society, contrasting them with the illegitimate chains of contemporary governance.

Rousseau’s theoretical challenge was to find a form of association capable of defending and protecting each individual’s person and property while ensuring that each person, in uniting with all, could still obey themselves and remain as free as before through a social contract. This contract requires “the total alienation of each associate, together with all his rights, to the whole community.” Each individual gives themselves to all, thereby giving themselves to no one in particular. As Rousseau explains, “As there is no associate over whom he does not acquire the same right as he yields over himself, he gains an equivalent for everything he loses, and an increase of force for the preservation of what he has.”

In essence, participants in the social contract agree to place their person and all their power at the common use, under the supreme direction of the General Will, with each member being viewed as an indivisible part of the whole. As a result, the private individual ceases to exist; the contract generates a moral and collective body that gains its unity, common identity, life, and will from this act. This public person formed from the union of all individual members becomes the State when passive, the Sovereign when active, and a Power when compared with similar institutions.

After establishing a state, Rousseau envisions a significant transformation in human beings. This transformation replaces instinct with a rule of justice, bestowing a moral character to actions that were previously lacking. He goes so far as to say that humanity evolves from a “stupid and limited animal” into an intelligent being.

However, Rousseau acknowledges that this transformation would be implausible if the contract were viewed as a singular event. Instead, he posits that the social contract represents a way of thinking, indicating that it is a process rather than an isolated occurrence. Consequently, the evolution of human nature occurs gradually alongside the deepening of social relationships, fueled by ongoing participation in the General Will. This perspective presents a vision of humanity whose moral sensibilities and intellectual capacities evolve in tandem with the expanding nature of their social interactions.

Popular Sovereignty

Rousseau introduced the radical concept of Popular Sovereignty, significantly shaping modern political thought. For him, sovereignty resided not in a distant monarchy but directly within the political community. He synthesized John Locke’s idea of popular government and Thomas Hobbes’ notion of absolute sovereignty to formulate his concept of Popular Sovereignty.

Rousseau asserted that sovereignty originates from the people themselves, not as a gift from natural or divine laws, but as an organized power derived from the collective will. This supreme authority empowers the people to determine right from wrong, making them responsible for lawmaking, enforcement, and adjudication. He referred to this as cosmic sovereignty.

Rousseau famously stated, “the moment there is a master, there is no longer a sovereign,” illustrating his departure from Hobbes and Locke. In Hobbes’s view, people create a sovereign and relinquish their powers to him, while Locke’s social contract establishes a limited government for specific purposes but avoids equating sovereignty—whether popular or monarchical—with political absolutism. In contrast, Rousseau’s sovereign is the people, formed into a political community through the social contract.

Unique among political thinkers, Rousseau regarded the sovereignty of the people as inalienable and indivisible, asserting that they cannot transfer their ultimate right to self-governance. Unlike Hobbes, who proposed a ruler as sovereign, Rousseau maintained a clear distinction between sovereignty, which resides entirely with the people, and government, a temporary agent of that sovereignty.

Rousseau also emphasized that since the sovereignty of the General Will is inalienable and indivisible, it cannot be represented or delegated. He criticized representative assemblies for developing their own particular interests, thus forgetting the community’s needs. This is why he favored direct democracies, such as those in Swiss city-republics, despite their anachronism during the rise of modern nation-states. He insisted that any attempt to delegate the General Will signifies its end, famously stating, “the moment there is a master, there is no longer a sovereign.” For Rousseau, the “voice of the people” embodies the “voice of God,” emphasizing the profound connection between popular will and moral authority.

Challenging Representative Government: The Call for Direct Democracy

Rousseau’s critique extended to the prevalent systems of government in his time, particularly the English Parliamentary System. He argued that these systems offered a mere illusion of freedom. In reality, people were only free during elections, and once they elected their representatives, their freedom dwindled. Rousseau advocated for a more direct form of democracy where people actively participated in the decision-making process.

He championed participatory democracy, a system that not only secured individual freedom but also promoted self-rule, equality, and virtue. In his view, true democracy required the active involvement of citizens in shaping the laws that governed them.

Rousseau’s views on Family and Women

Rousseau, like Aristotle, considered the family as the fundamental unit of society. He defended the patriarchal family structure, seeing it as a natural institution grounded in love, affection, and the inherent differences between the sexes. However, his stance on women in society mirrored the prevailing views of his time. Rousseau assigned a subordinate position to women, both in the family and society at large, with male authority prevailing.

Rousseau believed that women should be represented by men in a liberal democracy, and he discouraged their participation in politics. His rationale stemmed from a fear that women would prioritize the interests of their families over the public good, unable to transcend their love and affection for the particular to embrace the general.

Critical Appreciation

Rousseau’s philosophical journey reveals a fundamental logical divide between his earlier work, Discourse on Equality, and his later work, The Social Contract. Vaughan notes that while the former is characterized by “defiant individualism,” the latter embraces “equally defiant collectivism.” However, Rousseau himself did not perceive this opposition; in his Confessions, he asserts that the strong ideas in The Social Contract were previously articulated in Discourse on Equality. Sabille supports Rousseau’s viewpoint, yet acknowledges the presence of seemingly contradictory ideas in his writings.

The distinction between the two works lies in Rousseau’s transition from freeing himself from systematic individualism to formulating a counter-philosophy. Systematic individualism, as criticized by Rousseau, posits that humans are moral and rational beings motivated by enlightened self-interest, leading to the creation of a community primarily for the protection of rights and promotion of happiness. Rousseau contended that this framework did not align with human nature. He argued that attributes such as rationality and self-interest are acquired through societal living rather than being inherent traits.

Rousseau challenged the notion that reason alone could unify individuals focused solely on their happiness, emphasizing that self-interest is as socially constructed as the innate social needs that bring people together. He posited that human sociability is based on feelings, not reason. In his analysis, he rejected Hobbes and Locke’s views of the state of nature, asserting that the Hobbesian portrayal of man as a natural egoist is a fiction.

Drawing insights from classical Greek thought, Rousseau emphasized that individuals achieve their true nature only within a community, where rights, freedom, and morality are cultivated. He maintained that the community serves as the primary moral agent and stressed the necessity for collective thinking about public good rather than individual interests.

Rousseau’s concept of the General Will aims to reconcile authority and freedom, but it inadvertently lends itself to totalitarian interpretations. Critics argue that his theory could justify coercive governance, with Sabine highlighting that dissenting moral views might be seen as capricious and suppressed.

Despite criticisms, Rousseau’s significance endures. Ebenstein points out that he was the first modern thinker to attempt to synthesize good governance with self-governance through the General Will. Furthermore, he highlighted that government must not only protect individual liberties but also promote equality. Rousseau’s reflections on civil society’s limitations resonate today, urging vigilance against executive overreach and the need for moral integrity in governance.

Famous Quotes by Rousseau

- ‘Man is born free and everywhere is in chains’.

- ‘I prefer liberty with danger than peace with slavery’.

- ‘I would rather be a man of paradoxes than a man of prejudices’.

- ‘No man has any natural authority over his fellow men’.

- ‘Our greatest evil flows from ourselves’.

- ‘Everyman has a right to risk his own life for the preservation of it’.

- ‘What wisdom can you find that is greater than kindness’.

- ‘The moment there is a master, there is no longer a sovereign’.

- ‘Voice of the People may be the voice of the god’.

- ‘The larger the state, the less the liberty’.

- ‘The strongest is never strong enough to always be the master, unless he transforms strength into right, and obedience into duty’.

Conclusion: Rousseau’s Vision of a Just Society

In conclusion, Rousseau’s political philosophy envisioned a moral and just society, one that prioritized the welfare of all individuals. He sought to transform human nature from a narrow, self-seeking state into a public-spirited one. His writings challenged the modern institutions of his time, exposing their shortcomings in delivering on promises of democracy, liberty, and equality.

Rousseau‘s state represented the pinnacle of human existence, a source of morality, freedom, and community that not only resolved conflicts but also liberated the individual. He emphasized the close relationship between liberty and equality, arguing that without equality, true liberty could not exist. His philosophy aimed to reconcile individual interests with the broader interests of society, promoting a harmonious coexistence.

Yet, Rousseau’s ideas were not without paradoxes. He championed the inalienable right to freedom while acknowledging that individuals could be forced to be free. He considered reason unnatural and artificial but recognized that without it, moral development was impossible. These paradoxes underscore the complexity of Rousseau’s thought and its enduring influence on political theory and the quest for a just society.

Read More: